George R. R. Martin’s Wild Cards multi-author shared-world universe has been thrilling readers for over 25 years. Now, in addition to overseeing the ongoing publication of new Wild Cards books (like 2011’s Fort Freak), Martin is also commissioning and editing new Wild Cards stories for publication on Tor.com!

Daniel Abraham’s “When We Were Heroes” is an affecting examination of celebrity, privacy, and the different ways people deal with notoriety and fame—problems not made easier when what you’re famous for are superpowers that even you don’t fully understand.

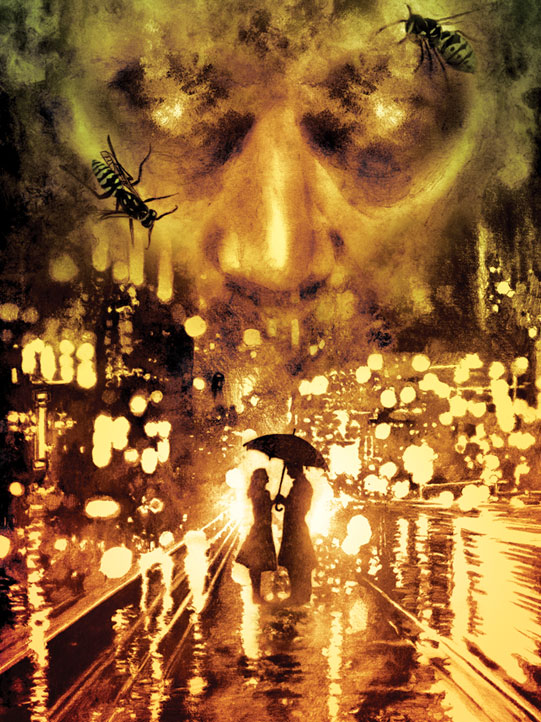

Manhattan smells like rain. The last drops fall from the sky or else the rooftops, drifting down through the high air. With every step, her dress shoes throw out splashes from the thin, oily puddles. It’s ruining the leather, and she doesn’t care. Her fingers, wrapped around her smartphone, ache, and she wants to throw it, to feel the power flow through her arm, down out along the flat, fast trajectory, and then detonate like a hand grenade. She could do it. It’s her wild card power. She’s not in the outfit she uses at the exhibitions and fund-raisers. She doesn’t look like a hero now. She doesn’t feel like one.

The brownstone huddles between two larger buildings, and she stops, checking the address. The east side, north of Gramercy Park, but walking distance. She always forgets that he comes from money.

The steps leading to the vestibule are worn with time and dark green with the slime of decomposed leaves. An advertisement for a new season of American Hero covers the side of a bus with the soft-core come-ons of half a dozen young men and women. Sex sells. She walks up the steps and finds the apartment number.

Jonathan Tipton-Clarke, handwritten in fading green ink. When he’s being an ace, he calls himself Jonathan Hive. No one else does. Everyone calls him Bugsy. She stabs in the code on the intercom’s worn steel keypad.

For a moment, she thinks he’ll pretend he’s not there, and she wonders how far she’ll go. Rage and betrayal and embarrassment flow through her. Breaking down his door would be illegal. It would only make things worse.

But still . . .

“Hey, Kate,” Bugsy says from the intercom.

“Are you looking at me right now?”

“Yeah. I’ve got one on the wall. Just to your left.”

A tiny, acid-green wasp stares at her. Its black eyes are empty as a camera. Its wings shift, catching the morning light. Jonathan Hive, who can turn his body into a swarm of wasps. Jonathan Hive, who was there when they stopped the genocide in Egypt. Who fought the Radical in Paris and then again during the final battle in the Congo. Kate lifts her brows at the wasp, and Bugsy’s sigh comes from the intercom. The buzzer sounds resigned, the bolt clicks open. She pulls the door open, pauses, and flicks a tiny wad of pocket lint from between her fingers. It speeds to the wall and detonates like a firecracker. She can’t tell whether the wasp escaped.

His apartment is on the fourth floor and she takes the stairs three at a time. When she gets there, she’s not even winded. He’s waiting for her, the apartment door standing open. Hair wild from the pillow. Lichenous stubble. Bloodshot eyes. His bathrobe was white, is grey. Wasps shift under his skin they way they do when he’s nervous.

“Come on in. I’ll make you some coffee.”

She holds out her phone, and he takes it. The web browser is at the mobile site for Aces! magazine. In the image, she is standing on the street by a small park, kissing a man. His face is hard to make out. Hers is unmistakable. The headline is DANGEROUS CURVES.

Underneath it, the byline is his name. And then the first few lines of text:

There’s nothing more American than baseball, explosions, and first date hookups. Well lock up your sons, New York. Everyone’s sweetheart is on the town, and she’s looking for some man action!

“What the hell is this?” she asks.

“The end of a good night?” he says, and hands it back.

Twelve hours earlier, she’d stepped out of an off-off-Broadway theater onto the Sixth Avenue sidewalk. Traffic was stopped on Spring Street, and backed up for more than a block, the air filled with braying horns and the stink of exhaust. Clouds hung over the city so low, it seemed like someone on the Chrysler building could reach out a hand and scratch them. Above her, the marquee read Marat/Sade, black letters on glowing white, then underneath it, NYC’s Only All-Joker Cast! She paused on the sidewalk, her hands in the pockets of her jeans, cleared her throat. Outrage and disbelief warred in her mind, until she shook her head and started laughing.

“It’s always kind of a confrontational play,” a man’s voice said. She’d been aware of someone coming out to the street behind her, but hadn’t particularly taken notice of him. Middle twenties. Dark hair that looked good unruly. Friendly smile.

“Confrontational,” she said, laughing around the word.

“Not always that confrontational. This production was a little . . . yeah.”

Curveball pointed at the theater.

“Did I miss something,” she said, “or were they actually throwing shit at us?”

The man looked pained and amused at the same time.

“Cow pats. I think that technically makes it manure,” he said. “It’s always rough when you’re trying to out-Brecht Brecht.”

Tomorrow was her exhibition show, the last one on this leg of the tour. She’d been planning to go out with Ana as her local guide, but her friend had been called out of town on business at the last minute and wouldn’t be back until morning. Kate had decided to make it an adventure. Grab a cheap ticket from the same-day kiosk on Water Street, take herself out to dinner someplace, spend an evening on the town. She had enough money to splurge a little, and she wasn’t in Manhattan often enough anymore for it to seem normal. The title Marat/Sade had seemed interesting, probably because of the slash. She hadn’t known anything about it, going in. Then the lights had gone up, and things got weird fast. For instance, the Sade half was actually the Marquis de Sade.

And it was a musical.

“Was there a point to that?” Kate asked, leaning against the streetlamp.

“The cow pats in particular?”

“Any of it?”

“Sure, if you look at the script,” he said. “Marat’s heading up the Terror after the French Revolution. De Sade’s . . . well, de Sade. They’re kind of the worst of political life and the worst of private life put together for comparison. I actually wrote a paper on Peter Weiss back in college.”

“And the shit flinging?”

“The deeper structural message can be lost, yes,” he said with a grin.

From down the block, a young black man in a sand-colored shirt waved.

“Tyler!”

The dark-haired man turned and held up a finger in a just-a-minute gesture. Tyler. His smile was all apology.

“I’ve got to go,” he said, and Curveball lifted a hand, half permission, half farewell. Tyler paused. She felt a moment’s tightness and the giddiness faded. She knew what came next. I’m a big fan. Can I get a picture with you? She’d say yes, because she always did because it was polite.

“Some of us are heading over to Myko’s for drinks and cheap souvlaki,” Tyler said. “If you want to come hang out, you’d be welcome.”

“Um.”

“They don’t throw manure. That I’ve noticed.”

Do you know who I am? slid to the back of her tongue and stopped there. He didn’t. Tyler’s friend called for him again.

“Sure,” she said. “Why not?”

Bugsy’s apartment smells stale. She wants to make the scent into old laundry or unwashed dishes, but it isn’t that. It’s air that has been still for too long. The kitchen is in the uncomfortable place between dirty and clean. A radio in a back room is tuned to NPR. In the main room, there are piles of books on the coffee table. Murder mysteries, crossword puzzles. The DVD of a ten-year-old romantic comedy perches on the armrest of the couch, neither box nor sleeve in sight. He starts a coffee grinder, and the high whining of hard beans being ripped apart makes speech impossible for a few seconds. The silence rushes in.

“You’re working for Aces!,” she says, even though they both already know it.

“I am. Reporting to the public at large which of their heroes are going commando to the Emmys. Keeping the world safe for amateur celebrity gynecologists.”

“Does the Committee know?”

The coffee machine burbles and steams. Bugsy grins.

“You mean the Great and Glorious Committee to Save Everyone and Fix Everything? I kind of stepped back from that.”

There is a pause. Just like you did hangs in the air like an accusation, but he doesn’t push it.

“What happened?”

She means What happened to you? but he seems to take it as What happened to your job? Maybe they’re the same question. He pours coffee into a black mug with the gold-embossed logo of a bank on the side and hands it to her. She takes it by reflex.

“Well, there was this thing. It was about six months after we took out the Radical,” he says. “Lohengrin called me and a few other guys in for this sensitive Committee operation at this little pit outside Assab.”

“I don’t know where Assab is,” she says. The coffee warms her hands.

“So you get the general idea,” he says, leaning against the counter. His fingernails are dirty. She’s known him for years, but she can’t remember if it’s normal for him. “Idea was to get some kind of industrial base going. Fight poverty by getting someone a job. You wouldn’t think there’d be a lot of push back on that, but there was. So essentially what you’ve got is this textile plant out in the middle of the desert with maybe two hundred guys working there, and five aces set up to do security until the locals can figure out what a police force would look like. I was half of the surveillance team.”

“Was this the fire?” she asks.

He smiles, happy that she’s heard of it.

“It made the news a couple of times, yeah. No one much noticed. It happened the same week Senator Lorring got caught sending pictures of his dick to that guy in Idaho, so there were more important things going on.”

“I saw it,” she says. “Someone died.”

“Bunch of folks died, but most of them were African, so who gives a shit, right? The only reason we got a headline at all was Charlie. An ace goes down, that’s news. Nats kill him, even better.”

Her phone vibrates. She looks at it with a sense of dread, but the call is from Ana’s number. Relieved, she lets it drop to voice mail.

“They had us in this crappy little compound,” Bugsy says. “Seriously, this apartment? Way bigger. The place was all cinder blocks and avocado green carpet. Ass ugly, but we were only there for a couple months. Charlie was a nice kid. Post-colonial studies major from Berkeley, so thank God he was an ace or he’d never have gotten a job, right? Mostly, he hung around playing Xbox. He was all about hearing. Seriously, that guy could hear a wasp fart from a mile away.”

“Wasps fart?” she says, smiling despite herself. He always does this, hiding behind comedy and vulgarity. Usually, it works.

“If I drink too much beer. Or soda, really. Anything carbonated. Anyway, Charlie was my backup. My shift, I’d send out wasps, keep an eye on things. His, he’d sit outside with this straw cowboy hat down over his eyes and he’d listen. Anything interesting happened, and we’d send out the goon squad to take care of it. We had Snowblind and a couple of new guys. Stone Rockford and Bone Dancer.”

“Stone Rockford?”

“Yeah, well. Be gentle with the new kids, right? All the cool names are taken. Anyway, first three days, there were five attacks. Usually, they’d aim for right around shift change when there were a lot of guys going in or coming out. Then two and a half weeks of nothing. Just East African weather, energy from a generator, and a crappy Internet connection. We figured we had it made. Bad guys had been driven back by the aces, they’d just stay low and act casual until the police force was online and hope they were a softer target.

“I was the senior guy. Been there since the Committee got started. Since before. Charlie gave me a lot of shit about that. How I was all hooked in at the United Nations. Big mover and shaker. And, you know, I think I kind of believed it, right? I mean it’s not just anyone can go into Lohengrin’s office and steal his pens. I was out there making the world a better place. Doing something. Saving people. Boo-yah, and God bless.

“You know what they sent us to eat? Sausages and popcorn. We had like fifty cans of those little sausages that look like someone made fake baby fingers out of Silly Putty and about a case of microwave popcorn. I mean seriously, how are you going to strike a blow for freedom and right when you’re fueling up on popcorn and processed chicken lips, right?”

She drinks the coffee, surprised by how bad it is. Bright and bitter. She expects him to distract her from the picture of her kiss with the tragedy in Africa, so it surprises her when he’s the one to go back to it. Maybe he’s trying to distract her from what happened in Africa. Maybe he’s distracting himself.

“It’s not actionable,” he says, nodding to her phone. “You can ask any lawyer anywhere. You were in public. There’s no legal expectation of privacy.”

“Do you think that’s the point?”

He looks away, shrugs. “I’m just saying it was legal.”

She leans against the wall, unfinished red brick scratching her shoulder. She thinks of the cinder block in the compound and the exposed ductwork at Myko’s, the thick, muddy coffee she drank the night before and the one in her hand now.

“Were you following me?” she asks.

“You think? Of course I was following you.”

“Why?”

He almost laughs at her. It’s like she’s asking where the sun will rise tomorrow, if he’s breathing, whether summer is colder than winter. Anything self-evident.

“Because you’re in town. I mean the whole point is to get stories about aces. We’re public figures. Most weeks, I have to find something to say about the people who are in the city. There’s only so many issues in a row that the readers are going to care about whether Peregrine’s hit menopause. Someone new comes in, I’d be stupid not to check up, see if anything’s interesting. I was thinking I’d just write up the exhibition thing this afternoon. The fund-raiser. But this is way better.”

When the anger comes back, she notices it has died down a little. She tries not to think what Tyler will say about the article. How he’ll react. The fear and embarrassment throw gasoline on the fire.

“When I’m at work,” she says, forming each word separately, “you can come to work. This is my private life, and you stay out of it.”

“Wrong, friend. That’s not how it is,” Bugsy says. The sureness in his voice surprises her. “Everyone knows who we are. They look up to us or they hate us or whatever. You’re not doing these exhibition things because people just love seeing stuff blow up. They can blow stuff up without you any day of the week. They come to see you. They pay to see you. You don’t get to tell them they care about you one minute and not the next. It’s their pick whether they pay any attention to you at all, and you make your money asking them to. So don’t tell me that here’s your personal you and here’s your public you and that you get to make those rules. You don’t get to tell people what they think. You don’t even get to tell people whether they admire you.”

With every sentence, his finger jabs the air. The buzz in his voice sounds like a swarm. Tiny green bullets buzz around them both, curving though the air. His chin juts, inviting violence. She can see how it would happen: the toss of the mug, his body scattering into thousands of insects, the detonation. Her own anger reaches toward it, wants it. The only thing that holds her back is how badly he wants it too. He’s trying to change the subject.

She laughs. “Hey, Bugsy. You know what the sadist said to the masochist?” He blinks. His mouth twitches. He doesn’t rise to the bait, so she acts as if he had. She leans forward. “No,” she says.

“I don’t get it.”

“We’re aces, so everybody knows us. We don’t get to pick how they feel. We’re still talking about Charlie, aren’t we?”

Myko’s was a small place with a dozen tables smashed into enough space for half that number. Posters of Aegean-blue seas hung from the walls by scotch-taped corners. The walls were white up to the six-and-a-half-foot mark where the drop ceiling had been ripped out, exposed ductwork and wires above it. Crisp-skinned chicken and hot oregano thickened the air and made the wind picking up outside look pleasantly cool.

“I don’t know why the hell I let you talk me into these things,” Tyler’s friend said. She hadn’t asked his name, and hadn’t offered hers. The other two at the table were a Lebanese-looking woman named Salome and a joker guy in a tracksuit that they all called Boss. He wasn’t really that bad looking, for a joker. All the flesh was gone from one of his arms, and his skin was a labyrinthine knotwork of scars. He could almost have been just someone who’d survived a really horrific burn.

“Did I talk you into something?” Tyler said.

“You did say it was a cool play,” Boss said.

“It is a cool play,” Tyler said. “It’s just a lousy production.”

Everyone at the table except her and Tyler laughed, and his glance thanked her for her tacit support.

“You are the only person I know who’d make that distinction,” Salome said. “When you say ‘this is a cool play,’ I think you mean, ‘it would be cool to go to this play.’ What was that whole whipping him with her hair thing about?”

“They took that from the movie,” Tyler said.

“There’s a movie?” Tyler’s nameless friend said, his eyes going wide.

“Look, I understand that it’s kind of an assault on the senses,” Tyler said. “That’s part of the point. Weiss wanted to break through the usual barrier between the audience and the actors. Not just break the fourth wall, but burn it down and piss on the ashes.”

“That sounds like the play I just watched,” Boss said.

The waiter swooped in on her left, piling the ruins of their dinner on one arm and unloading demitasses of dangerous-looking coffee and plain, bread-colored cookies from the other. His hip pressed against her shoulder in a way that would have been intimate in any other setting and didn’t mean anything here.

“I don’t know,” she said. “I can understand the idea of trying shake up people’s expectations, but then I sort of feel like you have to do something with them. Sure, the actors did stuff actors don’t usually do.”

“I think one of them went through my purse,” Salome said.

“But,” Kate went on, holding up her finger, “wait a minute. Then what? Is it just breaking barriers for the fun of breaking them? That seems dumb. If someone sneaks into my house, it breaks a bunch of usual barriers too. It’s what you do after that matters. If you keep on assaulting people after that, it’s almost normal.”

“At least it’s not unexpected,” the nameless friend said, nodding.

Boss laughed. “Now you get the actors to come home with me and paint my bathroom, then you’ll defy expectation.”

She sipped the coffee. It was thick as mud and honey-sweet. Something buzzed next to her ear. She waved her hand absently and it went away.

“I can see Carol’s point,” Tyler said, “but that gets back to the production choices.”

“Who’s Carol?” Tyler’s friend asked.

Tyler’s brow wrinkled and he nodded toward Kate. “Carol. You know. Siri’s roommate from Red House.”

The quiet that fell over the table was unmistakable.

“I don’t know anyone named Siri,” she said, smiling to pull the punch. “My name’s Kate.”

Tyler’s mouth went slack and a blush started crawling up his neck. Salome’s giggle sounded a little cruel.

“Well,” Tyler said. “That’s . . . um . . . Yeah.”

“I thought you were playing it awfully smooth,” Tyler’s friend said, and then to her, “My boy here isn’t a world renowned pick-up artist. I wondered what gave him the nerve to break the ice with you.”

“I’m sure Carol will be very flattered,” Kate said. “And for what it’s worth, I thought it was pretty smooth.”

“Thank you,” Tyler said, blushing. “I hadn’t actually meant it as a pick-up thing.”

“Or you would have cocked it up,” his friend said.

“Isn’t Carol the one with the big teeth?” Salome said. “She doesn’t look anything like her.”

“Carol’s teeth aren’t that big,” Boss said. “You just didn’t take to her.”

“Regardless,” Tyler said, turning to her, “Kate. I’m really glad you came with us, even if it was only to see me make a jackass out of myself in front of my friends.”

She waved the comment away. A gust of wind blew the door open a few inches, the smell of rain cutting through the air. Salome and Boss exchanged a glance she couldn’t parse. Dread bloomed in her belly.

“It’s just you looked really familiar,” he said, “and I thought—”

“I get that a lot,” she said, a little too quickly. The moment started to fishtail.

“I guess . . . I mean, I guess maybe we ran into each other around the city somewhere. Do you ever hang out at McLeod and Lange? Or—”

Boss’s laughter buzz-sawed. The joker shook his head. “Jesus Christ, Tyler. Of course she looks familiar. You’re hitting on Curveball.”

In the press and noise of the restaurant, the pause wasn’t silent or still, but it felt that way. She saw him see her, recognize her. Know. His face paled, and she lifted a hand, waving at him as if from a distance. The regret in her throat was like dropping something precious and watching it fall.

“Oh please,” he says. “I’m talking about anyone. Charlie. You. Me. Hell, I’m talking about Golden Boy. He’s been around so long, he’s lapped himself. He was saving America from evil, then he was a useless sonofabitch who ratted out his friends, then he was nobody, and now he’s so retro-cool he’s putting out an album of pop music covers. You think he had control over any of that? It just happens. It just . . .”

He shakes his head, but she isn’t convinced. She’s known him too long.

“You know all of us,” she says. “Michael. Ana. Wally. Not Drummer Boy and Earth Witch and Rustbelt. You know us.”

“Yeah, that’s part of why Aces! hired me on. You know, apart from the—” He makes a buzzing sound and shakes one of his hands, a fast vibration like an insect’s wing. “I know where all the bodies are buried. Or a lot of them, anyway. I know the stories.”

“You know the people.”

“For all the good it does,” he says, shrugging. “Lohengrin was pretty pissed off when I handed in my two weeks. Not that it was really two weeks. Two weeks at the UN is barely enough time to get a cup of coffee. Bureaucracy at its finest. Say what you will about the failings of tabloid journalism, it’s got a great response time.”

From the street, a siren wails and then a chorus of car horns rises. She has the visceral memory of being nine years old and listening to a flock of low-flying geese heading south for the winter. It’s a small memory she hasn’t told anyone about. It’s a thing of no particular significance. He drinks from his coffee cup. A bright green wasp crawls out of his skin, and then back in.

“Bugsy . . .” she says, and then, “Jonathan.”

He sits on his couch, pushing the books on the coffee table away with the heel of his foot.

“The glory days are gone anyway. The whole thing where a bunch of us see something wrong and we go fix it? Stop the genocide, save the world, like that? It’s over. Everything goes through channels now. Everyone answers to somebody. The Committee? Yeah, it’s a freaking committee. No joke. They don’t need me. People come in and out all the time. Join up for a mission or three, make some contacts, and go work for some multinational corporation’s internal security division for eight times the money. I’m not doing this whole thing for Aces! for the cash. I could get a hell of a lot more.”

“Labor of love?” she says. The sarcasm drips.

“Why not?” he says. “There are worse things to love. Your boy, for instance, seems nice. I mean in that clean-cut upwardly mobile nat-working-for-the-Man kind of way. The bazooka line was great, by the way. I thought that was really a good one.”

He’s goading her again, pushing her back toward her anger, and it works a little. She wonders for a moment how much the little green wasps have seen and heard. The sense of invasion is deep. Powerful. She’s embarrassed and insulted, and she imagines Tyler feeling the same way. If it were only her Bugsy’d held up for public judgment, it wouldn’t have been so bad. She wonders if Bugsy knows that.

He is soothing her and pricking at her, pushing her away and asking her in. He’s asking for help, she thinks. His bloodshot eyes meet hers and then turn away. He wants to tell her, and he doesn’t. He wants to have a fight so he can get out of a conflict. She’s not going to let him.

“That isn’t what happened to Charlie,” she says. “He didn’t get the job with a big corporation and get out.”

“No,” he says with a sigh. “That isn’t what happened.”

Watching his face change is fascinating. The smirk fades, the joking and the fear. The bad hair and the terrible stubble lose their clownish aspect. When he’s calm, he could almost be handsome. Despair looks good on him. Worse, it looks authentic.

“You were the senior guy,” she says, prompting him.

“I was the senior guy.” The words are slower. “I liked it. It wasn’t like having some kid in the crowd come up and ask for an autograph. This was Charlie. He was someone I knew. Someone I hung out with. I’d tell stories about the old days, and he’d actually listen. And he was a funny kid. He pulled his card when he was twelve. Got a fever and bled from the ears. His sister took him to the emergency room because their mom was working and they couldn’t get through to her. He thought he was going crazy. He was hearing people’s voices from half a mile away. He was hearing the blood in the nurse’s veins. By the time they figured out it was the wild card, there wasn’t anything for the doctors to do but shrug and move on. He was still walking around with these sound-killing earphones until he was seventeen. The way he talked about it, it seemed funny, but that stuff’s never funny at the time. Anyway, he went to college. Started getting seriously into the African experience, to the degree that you can do that from California. Dropped out of college, signed up to work for the Committee.”

She sips her coffee. She expects it to be cold, but it’s still warm enough. A man’s voice raised in complaint comes from down the hall, and she wonders whether they closed the apartment door. By reflex, she wants to go check, but she holds herself back. There’s something fragile in the moment that she doesn’t want to lose.

“Charlie just signed up?” she says, and Bugsy shrugs.

“He’s an ace, right? That’s what we’re looking for. The extraordinarily enabled set to achieve tasks that might otherwise be impossible. I got that from a press release. You like it?”

“Was your thing his first time out?” she asks, not letting him deflect her.

“No. He’d done something with tracking illegal water networks in Brazil. Listening for buried pipes. He talked about it some. The supervisor on that one was a nat, though. This was the first time he’d had other aces to work with. Those first few days when we were stopping the attacks? They were amazing. I mean, it was scary because there were guys with machine guns driving around in jeeps trying to kill the people we were there to protect, and if we screwed it up, bad things were going to happen. But we were winning. The textile plant kept running. The folks working there didn’t get killed. We were big damn heroes, and it was great.”

“Even with the lousy food.”

“Hell yes,” Busgy says. “Even with the lousy food. Even with the shitty Internet connection. We had three games on the Xbox, and a crappy little thirteen-inch screen to play them on. The beds were like the mats they give you at the airport when your flight’s cancelled and you’re going to be on the floor all night, and we were all so jazzed and happy, we didn’t even bitch about it. It was great. We were happy just to be there. And then it was quiet for a while.

“At first, we were still tense. Waiting for the other shoe to drop, right? And then after a couple weeks, we were all thinking that this was it. It was over. It was another month before the local police were going to take over, and we were all figuring that we were looking at another four weeks of sitting around doing nothing much. But I got sick. Not sick sick. Just stay-home-from-school stuff. Sore throat. Fever. Felt like I needed a nap every third minute. It sucked, but it wasn’t a big deal, and Charlie was up for covering me. Except he needed to sleep too sometimes. So I set up this plan. Sheer elegance in its simplicity. Charlie’d work his shift like usual. I’d do a half shift because I could stand that much, and then in the middle of the night when there wasn’t anything going on anyway, the other three—the goon squad, we called them—could head out to the plant and just keep an eye on things while I got a little extra shut-eye. A couple days of that, I’d get my feet back under me, and we’d go back to the usual thing. It wasn’t like there was anything happening anyhow.”

His gaze is fixed on nothing now, looking past her, though her. A wasp flies through the air, lands on the wall beside them, and folds tiny, iridescent wings. Its stinger curls in toward its own belly.

“No one pushed back,” he says. “We were all best buds by then. If Charlie’d been sick, we’d have covered for him. Or if one of the goon squad guys had come down with something, I’d have gone out in his place. I’m not bad in a fight, most of the time. It was just an obvious thing. Someone feels under the weather, you take on a little more. Something you do for your friends.”

“Sure,” she says.

“Sure.”

He swallows. There are no tears in his eyes, but she expects them so powerfully that for a moment she sees them anyway. He shakes his head.

“It was a textile plant,” he says. “They were making cheap T-shirts to sell in Europe. It gave a couple hundred African guys some folding money that they could spend in town. It put a little extra juice in the local economy. It’s not like we were going in there and burning down the churches or something. And the guys on the jeeps? The ones who didn’t like it? They didn’t even talk to us. All their preaching and outreach was in the city. We were just a part of the plant to them. There’s the building, and the guys that worked there, and the cloth going in and the shirts coming out, and then the aces that kept you from breaking all the rest of it. If they could have busted up the machines, they’d have done it and been just as happy. They didn’t even hate us. They hated something that we represented, and I don’t even have the framework to understand what it is.”

“Western imperialism,” she says.

“Maybe. Maybe not. Maybe I’ve got the whole damn thing wrong. For all I know, the guys in those jeeps were all born in Detroit. We were out there trying to do something good. They were trying to do something else. It was all about international trade and local autonomy and religion and nationalism. None of it was about what kind of people we were. Probably if we’d invited the bastards in, they’d have had a blast playing our video games, right? Sat around eating our nasty little sausages and shooting zombies.”

“But that’s not what happened.”

“No,” he says, and hunches forward. He sighs. “No, it isn’t. There was this one night, Charlie took his shift, put in his earplugs—he had these amazing industrial foam things that let him sleep—and hit the bunk. I spread out from just before sundown to almost midnight, then gathered back up, sucked down some Nyquil, and called it a night. The others headed out to the plant. Just like we planned.”

He lapses into silence, his eyes flickering back and forth like he’s reading letters in the empty air. She has known him for years. She’s wanted to like him more than she has. He doesn’t make it easy. She glances at her phone. The browser is up. DANGEROUS CURVES. She wonders whether feeling betrayed by him means that she does think of him as a friend. Or did, anyway.

“What happened?” she asks, annoyed with herself for the gentleness in her voice.

“It all went to hell.”

“Oh. My. God,” Salome said, laughter bubbling up with the words. “You really are, aren’t you? You’re Curveball?”

“I am,” she said.

Boss smiled at her, rolling his eyes like the two of them were in on a joke. He’d known it was her all along. It was these other rubes who hadn’t seen it. Tyler stared at the salt shaker and wouldn’t meet her eyes.

“Did you really date Drummer Boy?” Salome asked, leaning her elbows against the table. There was a hunger in her expression that hadn’t been there earlier, like she was seeing Kate for the first time that evening.

“Not exactly.”

“What’s he like?” Salome asked.

Kate smiled the way she did at public events, the way she did when someone asked for an autograph or a picture.

“He’s just like he seems,” she said. It was the same answer she always gave, one of the stock phrases she always kept at the ready. Salome laughed, just they way people usually did.

All the conversation shifted to her, the play forgotten, the meal forgotten. What was she in New York for? She was doing an exhibition show tomorrow at the park in support of a fund that was building schools in developing nations. Did she get to New York often? A couple times a year, sometimes more. It depended on the situation. The questions were familiar territory. The diplomacies and evasions and jokes that she’d used at a hundred photo ops.

Boss kept needling Tyler for not having recognized her, and Tyler grew quieter and more distant. In the end, he was the one who called for the check, totaled up what everyone owed, and said his goodnights. The others seemed perfectly willing to let him go. He nodded to her when he stood, but didn’t keep eye contact. When he walked out the door, a cool draught of air slipped in past him, smelling of rain.

“Well, you know, when I pulled my wild card—” Boss said, one scarred and misshapen finger tracing the air.

“Actually,” Kate said, “could you just . . . I mean. Excuse me.”

The sidewalk was shoulder-to-shoulder full. A wide curve of cloud looped between the skyscrapers, the lights of the windows turning misty as it passed. She caught a glimpse of Tyler’s dark hair, stopped at the corner, heading north. She hopped down to the gutter and scooted along, the taxis whizzing by her, inches away. When she called his name, he turned. Chagrin paled his face.

“Hey,” she said. “I just wanted to say thanks. For letting me tag along.”

The light changed, and the press of bodies surged around them. He glanced at the white symbol of a man walking, then back to her. Someone bumped against his back.

“Always pleased to have a few more at the ritual humiliation,” he said. There was no bitterness in his humor and only a little sorrow. “It was really great to meet you. And coming along with us was something I’m sure my immediate circle of friends will be bringing up for the rest of my natural life in order to tease me. But it was really cool of you.”

“Yeah,” Kate said. Behind him, the signal changed to a series of red numbers, counting slowly down. The pedestrian traffic thinned for a moment. A truck lumbered around the corner. She pulled back her hair, anxious and embarrassed to be anxious.

The red numbers crept toward zero.

“Do you want to go get a drink?” she said, rushing the words a little. “Or something?”

“You don’t have to do that,” Tyler said. “I mean, thank you, that’s really cool, but I’ll be just fine. I’m just going to head home and bury my head under a pillow for a couple days and resume my normal life as if I hadn’t made an idiot of myself. You don’t need to try and . . . You just don’t need to.”

“Oh. Okay, then. All right,” she said, nodding. She felt like someone had punched her sternum. And then, “But do you want to go get a drink or something?”

His smile was pretty, gentle and amused and melancholy. He had the kind of smile men got after the world bruised them a few times. The light changed, the flow of traffic shifted, pushing her a half step closer to him.

“I’m not that guy,” he said. “You hang out with aces and rock stars and politicians. I hang out with Boss and Salome. I’m nobody, you know? I’m just this nat guy trying to make rent in Brooklyn Heights and commuting into the city. You’re Curveball.”

“Kate, actually,” she said. “My name’s Kate. And I’m not whatever you think I am just because I’m an ace.”

An older black man with grey temples looked over at her, eyebrows raised, but he didn’t pause or try to ask for an autograph.

“But—” Tyler began.

“I’m Kate. My father’s Barney. My mother’s Elizabeth. I read Heinlein when I was a kid and stayed up late so I could watch Twin Peaks even though it gave me nightmares and I didn’t understand half of it. And I’m wandering around New York by myself because all my friends were busy, and I met this guy I kind of like, only I think he may be blowing me off,” she said, watching his eyebrows hoist themselves toward his hairline. “Drawing an ace isn’t that impressive. It’s just something that happens to people.”

“I just—”

“I don’t do anything that anybody else couldn’t do,” she said, and then a beat later, “I mean, if you gave them a bazooka.”

He laughed, and the sound untied something in her throat. He shook his head just as a wide, fat drop of rain patted onto the cement at their feet.

“Well, when you put it like that,” he said.

“What do you do? Your day job.”

He raised his hands in something like surrender.

“I work at a tech start-up that’s using social media to address inefficiencies in medical laboratory tests,” he said. “Honest to God.”

“Really?” she said. The light changed again. An insect buzzed past her ear. A police siren rose up somewhere not too far away. “I would have guessed something about theater.”

“I was a theater major when I was in college, but it didn’t end well.”

“No?”

“No,” he said, ruefully. “I got in a fight with my advisor. A real fight. He hit me.”

“Sounds serious,” she said, smiling. “What were you fighting about?”

“Tennessee Williams. We had different interpretations of The Glass Menagerie.”

“Is that the ‘always relied on the kindness of strangers’ one?”

“No, that’s A Streetcar Named Desire,” he said, and the rain began like someone turning on a faucet. Hard, wide drops falling through the air. Thunder muttered, even though she hadn’t seen any lightning. Tyler grinned. “Why don’t we go someplace dry. I’ll tell you the whole story.”

“We didn’t hear them coming,” Bugsy says. “I was sick and drugged. Charlie was asleep. It was the middle of the night, and we were complacent. Who in their right minds attacks a compound of aces, right? We’re the guys who can shoot laser beams out of our fingers or lift tanks or whatever. If you come at us, it’s with a bomb or something. Something fast. You don’t get a bunch of kids on bicycles with bottles of gasoline. C’mon. Fucking gasoline?”

He looks up at her, a goofy smile stretching his lips, false as a mask. A wasp crawls out of his tangle of hair and buzzes away. He shakes his head, looks down. She can tell that he wants her to say something, to divert the words spilling out of his mouth before the pebbles turn into a landslide, but it’s too late. He fidgets with the puzzle book on the coffee table. When he speaks again, the reluctance in his voice hurts to hear.

“You figure it all out later, right? I mean, we’ve got the tracks, and it was all little mountain bike snake trails. And the plastic jugs. They were like milk jugs. They poured it all around the outside of the building. And you know what’s weird? I can absolutely see them doing it. I mean, I can see them leaning their bikes against the wall. I can hear the gas making that glurp-glurp sound it does when you’re pouring everything out of one of them. I can smell it. I can smell the fumes coming off it even before they light the damn stuff. I was asleep. I didn’t see any of it, but I remember it just like I was there.

“First real thing I knew, Charlie was shaking me awake. He was wearing a Joker Plague t-shirt. How’s that for insult to injury? He was shaking me awake and telling me there was a fire and we had to get out, and Drummer Boy was on his chest looking like some kind of rock-and-roll god. It took me a little while to figure out what he was talking about, and then we were running around the compound—and it was like ten steps any direction, the place was that small. Everything outside was burning. It was like they’d dropped us in hell while we were sleeping. We closed the windows, and I tried to use the cell phone. I got through to the goon squad even, but the fire was so loud we almost couldn’t hear each other. Charlie was dancing around like a kid who needs to pee. I told them what was going on, but they were six miles away. They came as fast as they could.”

He rubs his fingers together, the roughness of his fingerprints sounding like the hiss of a book’s pages turning. A wasp appears in his fingers, conjured from his flesh. He looks at it like Hamlet staring at Yorick’s skull.

“They’re small,” he says, holding the insect out to her. Exhibit A. “When I bug out, really all the way out, I’ve got all this surface area. Can’t thermoregulate for shit. Get cold fast. Or I cook off. Seriously, too much heat, and I’m like popcorn.”

“You took off,” she says. “You left him.”

“I stayed as long as I could,” he says. “I couldn’t get him out. I couldn’t lift him. The fire was baking the place, and I had to go. I knew I had to go, but I couldn’t just leave him.”

“Except you did.”

“Except I did. Went out through the vent over the oven. Lost six percent of my body mass to bugs dying in the fire, and I just got out and flew straight up until I hit cold air. They were gone by then. The guys on the bikes? They were gone. I saw the goon squad’s jeeps booking it for the compound. I thought maybe they’d make it in time. Maybe they’d get him out.”

Busgy sighs.

“He didn’t burn,” he says. “The fire ate up all the oxygen, and he asphyxiated. They found him curled up on that nasty-ass little couch like he was asleep. He had a cover over him. He was in the middle of a fire, and he went and got a blanket? Why would you do that? What’s that even about?”

He takes a huge breath, lets it flow out from between his teeth.

“The attack was a diversion,” she says.

“You think? They had a second team ready. Torched the factory. Burned it to the foundations. Shot about a dozen maintenance guys. Huge embarrassment for the United Nations. Maybe half a billion in hard capital and trade agreements. Lohengrin had to give me a letter of formal reprimand. You could see it killed him to do it, but the secretary-general needed to blame someone, and they picked me.”

“I’m sorry,” she says.

“It’s all right. I had it coming.”

He stands. The floor creaks as he walks across it to the window. The insects in the room are silent, then one buzzes for a moment, like someone in the next room clearing their throat. The siren is gone. The car horns mutter at the low, constant mutter of the city.

“You know how many kids are living on the street in New York?” Bugsy asks. “Want to guess? Sixteen thousand. Just in New York City, center of the civilized world. And I can’t fix that. You know the climate’s changing, right? The Arctic’s melting, and it turns out there’s this freaking plume of methane coming up out of all the melting permafrost. I can’t fix it. There are a bunch of parents out there who aren’t getting their kids immunized because they’d rather watch little Timmy die of polio than do a little basic research. Can’t fix them. Most of Africa is hosed beyond belief, but what’re you gonna do, right?”

“We have to try.”

“Do we? I mean do we have to? You remember American Hero? That first season? Bunch of young aces trying to out macho one another. King Cobalt, dead. Simoon, dead a couple of times. Gardener, dead. Hardhat. We were trying to make the world better, and it killed us. You were one of the first ones to bail on the Committee, you know? And I think you were right.”

“I just needed some time off,” she says.

“Yeah, well,” he says. “Don’t go back.”

She doesn’t know how to reply. The anger is gone, and there’s a sense of shame. And sorrow. Maybe he means there to be, but it doesn’t matter. He walks back across the room, disappears into his bedroom, and reemerges with a tablet computer in his hand. On the screen, a dozen thumbnail photographs glow. They are all of her and Tyler. In one, they are going into the little neon-lit bar. In another, they’re coming out of it, huddling together under the cheap black umbrella they bought from a street vendor. His arm is around her shoulders. One of them is Tyler hailing a taxi. One is the kiss. She takes the tablet from him. She’s still angry, but without the headlines, without the joke about her ace nickname and the gossip column banter, it’s kind of a pretty picture. A man and a woman, kissing. If it were something private, it could be beautiful.

“I want to care about something that doesn’t matter,” Bugsy says. “I want to tell the word about which movie star got drunk with which ace. I want to debate whether American Hero should have another season and laugh about who had a wardrobe malfunction when they were meeting the president. I want to care about things I don’t care about.”

“Like me?” she asks, handing back the tablet.

He takes it. Looks at the pictures.

“Yeah, like you. Your love life, anyway,” he says, gently. He raises the tablet. He lifts his arms out, fingers reaching for the walls. He looks like a mocking image of Christ, crucified on the air.

“I’m done saving the world. I tried. It didn’t work. Now I want to live a small, petty life doing things I’m good at where if it goes south, no one dies.”

She crosses her arms. She isn’t sure whether the thickness in her throat is contempt or grief.

“No one’s going to stop you,” she says.

“It was nice, watching you. I mean not in a stalkery creepy number-one-fan kind of way. Just you and your boy out together. It was nice. It was . . .”

“It was?”

“It’s what’s supposed to balance out the shit, right? I don’t mean to get all ooey-gooey, but it’s the beginning of love. Or it could be, if you don’t screw it up. That’s the kind of thing that’s supposed to make all the sacrifices worthwhile. Make the world worth living in.”

He chuckles, and there’s amusement in the sound, but also disappointment. Bugsy had wanted something from her—forgiveness, maybe, or courage—and she doesn’t have it to give. He considers the tablet and taps at the picture.

“It probably doesn’t matter to you,” he says, “but I had them run the one where you can’t see his face.”

The worst of the storm passed while they were in the bar, but there was still enough rain to justify standing close to each other under the umbrella. Kate felt warm and a little freer than usual, but not tipsy. Tyler’s cheeks looked redder than when they’d started. Behind them, a small park sat, not even a half block deep, with skyscrapers on all sides, rising up into the clouds. The rain that still fell was cold, but soft. Across the street, the hotel rose up like a wonder of the world, the golden light from the lobby spilling out onto the wet, black street. Taxis whizzed by, throwing off spray. Men and women hurried by in black raincoats. Kate looked at the little green niche and thought how incredibly improbable it was to have a small bit of grass and ivy in all this concrete and asphalt.

When she turned, Tyler was looking at her. He had the look in his eyes—regret and hope and the small, unmistakable glimmer of a masculine animal. It was the end of the night. Neither of them wanted it to be, but the evening had a shape, and this was where that curve met the earth.

“I know you told me not to,” he said, “but really, thank you for not letting me go back to the apartment with my tail between my legs.”

“It wasn’t charity,” she said, laughing. “I had a good time. I don’t actually meet new people very much.”

“I’d never really considered the problem, but I can see how it would be difficult separating the Kate from the Curveball. I guess that’s why some aces have secret identities. Just so they can go get some groceries or hang out at the bar.”

“That’s part of it,” she said, pushing her hair back from her face. “Or to have room to be who they are. Not spend their whole lives filling the roles that people expect of them.”

“That’s not just aces, though. That’s the whole world.”

They were talking without saying anything, each syllable another tacit, doomed wish that the moment not end. Another taxi sped by, the black sludge spattering against the curb. A squirrel loped across the grass and took up a perch on the back of a green metal park bench. Everything smelled of fresh rain and car exhaust.

“So I should probably go,” he said. “I’m supposed to go into the office tomorrow, and they like me to show up on time.”

“Yeah,” she said. “And I’ve got the exhibition show. Be better if I went in rested.”

“Yeah.”

The rain tapped the sidewalk by their feet.

“It was really great meeting you, Kate. I’m glad I totally didn’t recognize you.”

“I’m glad you totally didn’t recognize me too,” she said.

“Do you want to keep the umbrella?”

“I’m just going across the street.”

“Right. Right.”

He squared his shoulders, steeled himself.

“If you’re going to be in town for a while,” he said, “I’d . . . Boy this is harder than it should be. I’d like to do this again.”

“You’re asking me out,” she said.

“I am. On a date. Because that’s just the kind of mad, reckless, carefree guy I am.”

“I’d love to,” she said.

“Oh, thank God,” he said. “I feel much better now.”

The squirrel jumped away into the darkness. They didn’t speak. They didn’t move.

“If this were a normal evening,” he said, “out with a normal girl, this would be the time that I kissed her.”

“It would,” she said.

He lowered the umbrella. His lips were warmer than she’d expected.

She walks over to the window, looking out at the city. Dread and embarrassment tap against her ribs like wasps against a windowpane, but not rage. The rage is gone. Manhattan is damp and shining as a river stone. The city is a symbol of the greatest powers of the world and of its darkness. The aces were born here, and the jokers. Shakespeare in the Park, and the terrible production of Marat/Sade. It is the city at the heart of the American century, and the target of all the tribes and nations that resent it. And what is it, really, but a few million private lives rubbing shoulders? For a second, the view through the glass shifts like an optical illusion, great unified city becoming a massive chaos of individuals and then flipping back as fast as a vase becoming faces.

She opens the window. A cool breeze stirs the air.

“We’re done, Bugsy,” she says. “This doesn’t happen again.”

“Of course it does,” he says. “You’re a public figure. You’re an ace. If it isn’t me, then—”

“It’s never you. And you never do it to him.”

“Tyler, you mean?”

“Tyler, I mean.”

He runs his hands through his hair. The cool air drives the free wasps back into him. She didn’t realize until now how much larger they make him. As they crawl back under his skin, he literally gets larger, but also seems to shrink.

“It was all legal. I didn’t do anything wrong,” he says petulantly. She doesn’t answer. He nods. “All right, but the boss won’t like it. If it’s not okay with you, pretty soon it won’t be okay with anyone, and then I’m out of a job.”

“You’ll find a way,” she says.

“Always do.”

Her phone buzzes again. Ana’s number. She ignores it. On her way past the couch, she puts her hand on his shoulder.

“Get some rest,” she says.

“Will. Don’t fuck it up, okay?”

In the street, she turns north, walking in the shadow of the buildings. A block down, a coffee shop presses out, white plastic tables and chairs impinging on the sidewalk. The closest they have to real brewed coffee is called a double americano, so she gets that. Her shoes are still wet from last night and this morning. She looks at the two messages from Ana, her friend. She wants to call back, but when she does, she’ll have to tell the story of what happened, and she still doesn’t know the end.

A taxi carries her back to the hotel. The exhibition is in five hours. She needs to be in prep in three. The hotel waits for her. The world does. She crosses four lanes of Manhattan traffic to get back to the little park. In the light, it looks smaller than it did at night. She sits on the green bench and takes out her phone, starts writing a text message, then deletes it and actually calls. He answers on the second ring.

“Hey,” Tyler says.

“Hey.”

“Did you know we’re on the Aces! website?”

She leans forward. She’s less than ten feet from where they kissed. She’s on a different world.

“Yeah, I just got finished kicking the reporter’s ass,” she says.

“I’m just glad he didn’t write it as a review,” he says. “It’s a little disconcerting to see my private life in the news.”

“It’s probably not the last time it’ll happen,” she says. If it’s too hard, I understand waits at the back of her throat, but the words won’t come out.

Somewhere in Brooklyn, Tyler groans. She’s faced armies. She’s had people with guns trying to kill her. This little sound from a distant throat scares her.

“Well,” he says, “this is going to take a little getting used to.”

“We’re still on, though?”

She’s afraid he’ll say no. She’s more afraid he’ll say Are you kidding? This is great. Across the street, the hotel staff is telling a beggar to move on. She can see into the lobby, where a television is tuned to a news channel, footage of fire and running bodies. She closes her eyes.

“I am if you are,” he says. “And . . . you are, right?”

“Like the world depends on it,” she says.

“When We Were Heroes” copyright © 2012 by Daniel Abraham

Art copyright © 2012 by John Picacio

The Sex and the City set-up — and then saying the radio was tuned to NPR? NYers who still actually listen to a radio are tuned to WNYC. They don’t say NPR.

And so on = doubtful.

I really liked it, nice juxtaposition of the two stories. First time I’ve ever read a (somewhat) sympathetic paparazzo.

(Might want to flag it for spoilers, maybe?)

Another good one Mr. Abraham. Thanks!

Men that turn to bugs girls that blow stuff up by flicking them… A virus that destroys 90 percent of a population and morphs the other 10 percent and where is there a question in the story? Are you sure he listened to NPR that seems inprobable… I Love It… Great story though a good quick read.

Love the Wild Card Universe! Wish there was a new story every week!

Really guys, you’re going to get hung up on the NPR thing? Shesh.

The story was another great Wild Card story, which I’ve always loved.

I never read the Wild Card comics, anyone know if they were any good?

Will these stories eventually be compiled into a physical book?

I am outraged that the alternate history New York doesn’t match my insignificant piece of trivia!

Cool story, I’m gonna try this Wild Card universe.

NPR fits the character. Bugsy is a guy who cares about the kinds of things that NPR reports. He’s out of the game, battling his own private demons, but he still keeps his ear to the ground because another part of him wants to continue being a hero.

Great story! I read the first three books years ago. May revisit the series.

Liked the feel of the story, not-overdone melancholy with just enough awsome and a sprinkle of love. Furthermore the dialouge felt real and not forced. I was not impressed by his writing on Leviathan Wakes so that’s a pleasant surprise (I thought it became way too blockbuster-ish, a lot of action and beautiful images, but little substance. To it’s defence though, it was entertaining), but that was with another author so mabye that’s why it felt different.

Also, I have never read a Wild Cards story, but I could still follow everything that happened and it was engaging. This made me want to look for more in this universe.

Best superhero story I’ve read yet. I just became a Daniel Abraham fan.

Always happy to read another tidbit to tide me over until the next book. Love the series! Thanks!

As a part of Wild Cards universe (which I haven’t read) it’s probably OK. As a stand-alone story in Anthology, it’s just another story about super-heroes, responsibility and love, which is nothing special.

Gave up after the first few paragraphs. The build-up was incredibly slow. Not sure if anything interesting happens later on. Life’s too short to read boring fiction.

Jonathan Hive was always my favorite of The Committee, while I found the John Fortune-Curveball-Drummer Boy love triangle less interesting, so I was a bit disappointed in the focus on the latter, and none of the former, in Lowball. So it was great to see why Hive traded in the U.N. for Aces!, and a really nice epilogue to the original Committee trilogy (still hope Hive & Lohengrin team up again in the next book/future).

(and while Hive might have called NPR radio WNYC, the scene was from non-New Yorker Curveball’s point of view, so she would have thought ‘NPR radio’)

This was one of the best stand-alone wild card short stories or novellas that I’ve ever seen. Admittedly this would not have the same impact for someone who read this without having read any of the wild cards universe but as a love-letter to those of us who have…Wow. Simply wow.

Thank you for the story! I am a huge Wild Cards fan, I own all the books and have been reading them since the 90’s. I’m currently reading Mississippi Roll and I started crying. One of the best things about the stories is how the characters grow, change, fail, or what ever life throws at them. I miss so many of the old characters but enjoy the new ones just as much.

Thank you for adding to that world!

Cory from Seattle.

This is so excellent!

Fantastic story. Handled very deftly. I really enjoyed it. Thank you.

I loved it. This is my single favorite short piece of Wild Cards fiction from Tor.com and I’ve read them all up through the Visitor. (Hey, what else y’gonna do while quarantined?) I’m sure it’ll never happen but I’d love to see what happens next for Curveball and her happily clueless gent.